This post was originally written as a flipped resources session for a teaching session I took with some Psychiatry Trainees.

The aim of this post and the teaching session is to touch on some practical issues in relation to becoming a better medical educator.

Presentations

There are many more bad presentations than good

Giving a presentation is a core skill for most doctors. It is something you are often requested to do, whether this be for some medical students, a Grand Rounds or a scientific meeting.

It is often said that there is a real “art” to giving a good presentation. But I’d like to call BS on that and suggest to you that actually its a science and we know a lot about what makes an effective presentation and most of the time we largely choose to ignore this.

Some resources you might find helpful include this wonderful TEDx Talk by David J Phillips on “How to Avoid Death By Powerpoint”. For me watching this video about 4 years ago was a game changer. It made a massive difference to my slide presentations, partly by paradoxically lengthening the number of slides (whilst reducingthe overall content). Before watching this video I had converted from powerpoint over to Prezi. But it turns out I was trying to solve the wrong problem. I thought that powerpoint made bad presentations. Actually its people that use powerpoint to make bad presentations. And to a lesser extent the default settings of powerpoint are also to blame.

Another great resource just released by Queensland Medical Educator Kate Jurd is this eLearning Resource.

If I was to give my 4 top tips for more effective presentations they would be this:

- Think firstly whether the presentation you are going to deliver will be enhanced by slides or whether it may be better (and more novel for the audience) if you don’t use slides. There are several other options, including just an oral presentation. I often find that if I have a good case prepared and perhaps a white board for demonstration purposes I can provide a more interactive and passionate and lively session.

- If you must use slides try not make your last slide “Any Questions”. This just creates doubt and ruins any impact you have just made. Leave the audience with the key point and a Call To Action.

- There are many great places to find creative commons licensed images to enhance a presentation. Pixabay is my general go to.

4. Light Text, Dark Background.

Some resources for improving your presentations:

The Informal Teaching Session

Many experiments have demonstrated that passion for one’s subject is the best means for engaging learners. Whilst, the results of these experiments have been overinterpreted to infer that students learn more effectively from engaged and passionate teachers. It remains likely that being a passionate teacher is one of the ingredients to effective learning.

There are 4 principles that form a good starting basis to an effective teaching or learning session which I always give to new medical educators. They are FAIR and are from Ronald Harden. You can source them from the following text (available in many medical libraries and from me if you ever work as an Education Registrar or the like with me).

Essential Skills for a Medical Teacher

Lets go through them in a bit more detail.

- F – Feedback

- A – Activity

- I – Individualisation

- R- Relevance

Feedback is fundamental as it can help to correct problems for learners, clarify learning goals and reinforce good performance (motivate learning). More on this later.

Active Learning has been shown to accelerate learning. By actively involving the learner in the process. By getting them doing things (rather than listening or observing) more cognitive processes are engaged. There are many options for “activating learners”. Here are a few ideas:

- Find out what the learner already knows about the topic

- Give the learner a problem to solve related to their new knowledge

- Give the learner a test

- Get the learner to carry out a procedure

- Ask the learner to reflect on their learning

- Ask the learner to share their knowledge with other students

Individualisation

- Where possible make sure that the learning your are involved with is attached to a clearly accessible and understandable syllabus. A syllabus is a document that communicates course information and defines learning expectations. Done well it can translate the curriculum into something actually understandable by students (as well as most teachers!). And usually includes a list of resources for the students to use to help them in their learning

- Provide a range of different resources in different modalities to assist learners. I often try to provide a mix of book recommendations along with blog posts and link to videos and where possible also examples of any assessments (if the course includes an assessment).

- Provide opportunities for the learner to come back and repeat the learning exercise.

Relevance is particularly important in view of the ever-expanding mass of medical knowledge. There is a temptation for everyone to view their own component of Medicine as vital for everyone else to know about. Some strategies that clinical educators may want to apply to ensure that their teaching is relevant, include:

- Asking the Learner. Medical Students and Trainee Doctors will be aware of the next gaps in their knowledge and have a reasonable view on what they are attempting to learn or master. Bear in mind that the learners view of what is important may not be the total picture and may often reflect what the learner perceives as the next steps in learning (see Zone of Proximal Development below) as well as what they think will be on the test.

- Obtain Feedback from the Learner. Find out from the learner if what you are teaching and in the way you are teaching is helpful.

- Find out what the learner needs to know. It is not uncommon to be confronted by a situation where there are learners who would like some impromptu teaching. In such circumstances, with no clear understanding of the curriculum, we tend to either ask the students or use our best judgement. This may lead to teaching and learning which is perhaps useful but not what the learner “needs” to know. If you regularly teach medical students or trainee doctors make enquiries about their curriculum, syllabus or learning outcomes. When you get your hand on a document like this find some things in it that you feel comfortable or passionate in teaching.

Feedback

Lets look at feedback in a bit more depth. Feedback is a core skill for anyone working in mental health. We use it constantly with our patients but its also an important skill for working with colleagues.

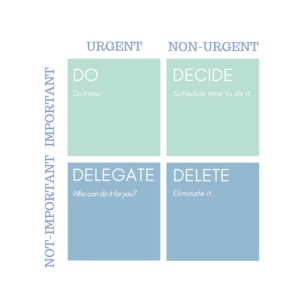

There are many models and approaches to feedback. There are none that really stand out in terms of being better than others. What is more important is how quickly or immediately you provide feedback. The closer to the activity the better as the student or learner will be able to better relate your feedback. As well as being specific. Although specific does not necessarily mean detailed. Sometimes you observe more than one thing that you would like to give feedback. Its often best to decide on the key piece of feedback. Be specific about that and leave the rest for another time. This helps to avoid “cognitive overload”. More about this below.

If you are starting out its probably a good idea to find a model that makes sense to you and use it. But bear in mind the need to be flexible in your approach.

One model I recently came across which I like is from Michael Gisondi at the ICE Net Blog and is called the “Feedback Formula”

- Ask permission

- State your intention

- Name the behavior

- Describe the impact

- Inquire about the learner experience

- Identify the desired change

To quote Michael a good summary of the research on feedback is:

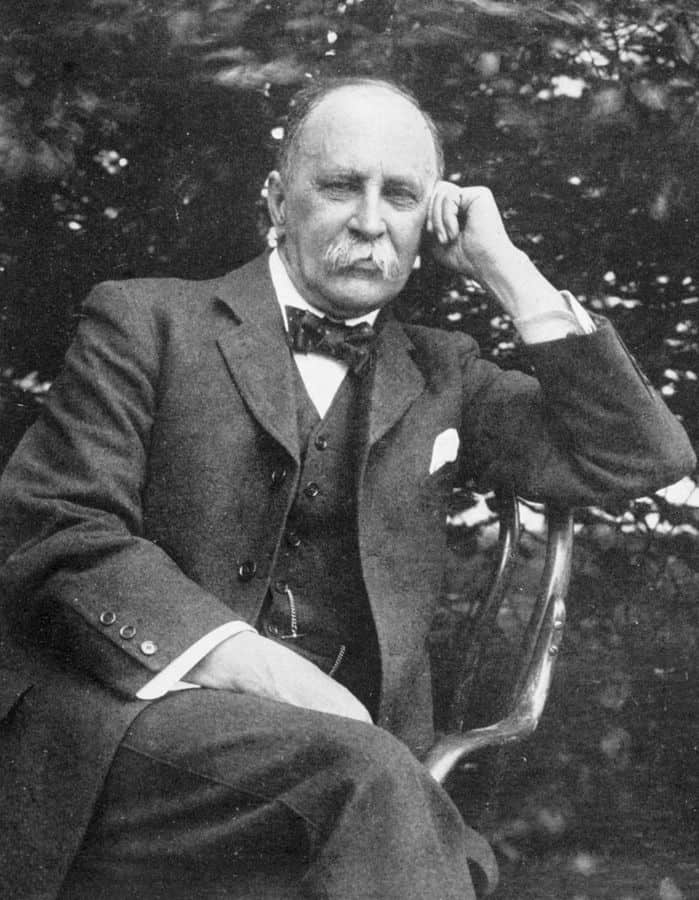

Michael Gisondi

(1) feedback is important, and (2) the quality of feedback varies widely.

Psychological Safety

One important principle of feedback is Psychological Safety. It is a term that you may hear a lot if you are ever involved in Simulation Training. Psychological safety is a shared belief amongst members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. It can be defined as “being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences of self-image, status or career”. In psychologically safe teams, team members feel accepted and respected. It is also the most studied enabling condition in group dynamics and team learning research.

If you are wanting to establish a psychologically safe space with a new learner (someone you are not familiar with). Be aware that it takes time to do so. A good rule of thumb is you need to ask a novice learner 3 times if there is something they wish to learn or are worried about before they will take you seriously. So persist.

The Basic Assumption

The Basic Assumption© was developed by the Center for Medical Simulation at Harvard. It is a useful concept to carry with you as you engage with feedback. It encourages you to have a curious mind when delving into the reasons for learners actions.

“I believe that trainees are intelligent, capable, care about doing their best and want to improve.”

Center for Medical Simulation, Harvard

Practice Your Feedback

Review some of the vignettes from the Teaching to Teach Series below and think about the process of feedback in each vignette.

First, think about the learner and what sort of feedback you would like to give them.

Then think about the teacher in the situation. How would you appraise their feedback skills? What feedback would you give them about their feedback?

The Intern – 3 Part Video Series

Teaching Medical Students

Learning Theory

In order to be a better clinical educator its worth knowing a little bit about educational theory. If you have read this post all the way through then you have already learnt some theory in relation to feedback, as well as Cognitive Load and Action Learning.

A great source to get started with Learning Theory is the ICE (International Clinical Educators) Net Blog which is supported by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

A good starting post is

In this post you will learn that knowledge is constructed (often socially) rather than transferred and learning involves a process of building new knowledge on top of existing knowledge. So new learning is influenced by past learning experiences. Authenticity and emotion can be useful tools to improve learning and retention of knowledge. Along with regular challenges (assessments) to ensure embedding of knowledge.

You will also read in this post that contrary to popular belief matching your teaching approach to learning styles is definitely not practical and probably not based in sound evidence. And also that Adult Learning Theory is probably not a great theory.

The ICENet also did a series of 9 posts looking at other relevant Learning Theories which are worth making your way through:

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Zone of Proximal Development

- Deliberate Practice

- Digital Natives

- Spaced Repitition

- Action Learning

- Transformative Learning

- Constructive Development

- Skill Acquisition

- Organisational Learning

- Self Determination

- Type 1 and Type 2 Thinking

- Gamification

- Self Directed Learning

- Reflective Practice

- Social Constructivism

- EQ & IQ

- Community of Practice

- Naturalistic Decision Making

- Modal Model of Memory