So you have settled into your new year at work. For some, this means the excitement of finally making it to an internship is still there. At least to some extent. For others, it’s the relief of having conquered that first year. Now being able to officially call yourself a Resident (apologies for use of NSW-centric terminology throughout this post). But your attention has already turned to that next hurdle in your career. Well, I’m guessing it has otherwise you probably would not be reading this post). We commonly refer to this hurdle as the JMO annual medical recruitment process.

Like every other hurdle in Medicine, the process can initially seem a bit daunting and unclear. But with a bit of planning of your time and seeking help, there are lots that you can do to ease the anxiety and maximise your chances of success.

You can Prepare for the JMO Annual Medical Recruitment Process with our Top 5 Tips

1. Work Out What Your Ideal Next Job Is (and then work out a fallback job)

In any goal setting its important to define early on What Does Success Looks Like? Its hard to put in place any reasonable plan without having a final objective in mind.

For those familiar with SMART Goals it’s important that we define something Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timebound. We won’t go over these 5 components in too much detail here. Measurable, relevant and time-bound are generally self-explanatory and established in the JMO Annual Medical Recruitment process in Australia and New Zealand.

Specific and Achievable are where you should focus your efforts. Many trainee doctors already have a fairly specific first preference job in mind. This is usually either to gain access to a basic specialty training program where the role is fairly broadly defined, or if you are further down the track a more defined Advanced Training position. (If you are still uncertain at this point, then that’s ok by the way. We will talk about what you can do to be more specific shortly).

If you do know already what your Ideal Next Job is. Ask yourself is this really achievable? Or to be more precise what if for some unforeseen reason it just doesn’t work out? Maybe your first choice is highly competitive or maybe you perform badly at interviews.

Have a Plan B

It’s important to have a backup or Plan B. So as an example let’s take Adult Basic Physician Training.

Your Goal might be stated like this

To secure a new contract by the end of this year to work in the area of Adult Internal Medicine either as a Basic Trainee or in an unaccredited SRMO role, so that I can continue to learn in this area that is of most relevance to me.

If you are uncertain about your Ideal Next Job or your Plan B, browse the JMO annual medical recruitment sites to see what sort of positions have been on offer in past years. This will give you a better idea of what is available.

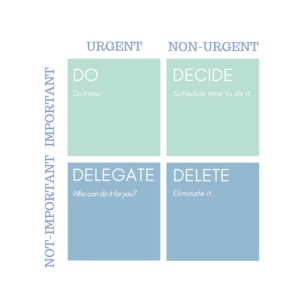

2. Plan Your Time Wisely in the lead up to JMO Annual Medical Recruitment

Now that we have our Goal we can make a plan and the first thing to do is work out how much time you have so you can prioritize and allocate your time appropriately.

Again a good starting point is to review the JMO annual medical recruitment websites for the positions you intend to apply for. In most jurisdictions or regions there will be some sort of jurisdiction-wide site through which trainees put in their application for jobs for the following year.

Here are a couple of examples:

Canterbury District Health Board

Look at these sites. In most cases, there is one date by which you must submit your application. Mark this down this is your first hard deadline from which you need to work backwards to ensure that you have everything you need (particularly a CV, Letter of Application and Referees). You probably need to aim to fit in pre-interviews or pre-meets before this date as well as there is usually not much time (or availability) to meet with a Director of Training once applications close.

The other dates you are looking for are the interview dates for the jobs you are applying for. They may not be well advertised so you may need to make some inquiries. These are also crucial as you will need to plan to take some leave from service to attend and you need to fit your interview practice in before these dates.

3. Work Out Who You Would Like to Ask to be a Referee

It seems obvious but we see so many medical trainees scramble to obtain referees at the last minute. You can help yourself out now by dropping an email or making a quick phone call to those people you have recently worked with or for.

Interns may not have had much contact so you are probably limited to a few key staff that you have worked with. For Residents, you probably have a few more choices.

You should try and line up at least 4 referees. These don’t need to all be a Fellow of the College you are aiming for. Other Fellows, Senior Trainees, Nurse Unit Managers, Senior Allied Health Staff are all good people to approach as a referee. Having a diverse range of referees on your CV looks better to most CV reviewers than a homogeneous mix of College Fellows.

At this point, you don’t need them to write you a reference (in a lot of cases they get emailed a form to fill out). Just make sure they will be happy when the time comes and check their contact details. If possible get a mobile number to put down. This makes it easier for anyone who wants to take a verbal reference.

4. Start Writing Or Revising Your CV

A good CV should always be tailored to the role you are applying for. This normally takes some time and several revisions to get right. You should also factor in time for someone else to proofread it for you and give you feedback. It’s likely that the CV you currently have will not be appropriate and need significant reshaping. Allow some time for this important task. Start thinking about what your Career Goal Statement looks like.

5. Start to Practice Talking About Yourself and Your Achievements

Start to think of the Interview as a form of high-stakes Viva Examination. Did you practice for these in medical school right? Well, you need to practice for the interview as well. There are lots of approaches to doing this. A good first step is to start thinking about your work and educational achievements. Think about how you can weave these into answers to interview questions. Many of us don’t normally like to “talk ourselves up”. So practising this activity makes sense and will help it come across as more authentic at the interview if you do.

Image Credit: janjf3 @ Pixabay