This week the Medical Board of Australia released the findings of the first-ever national medical training survey (MTS). As someone who has previously championed and developed these types of reports on the New South Wales level, it is truly pleasing to see this report launched. And boy did they release some findings!

With the results of 59 headline questions reported across several different segments, including interns, prevocational and unaccredited trainees, IMGs and specialty trainees. With the main report running 249 pages, several other reports drilling down to College level, State and Territory level and even an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander report. As well as an online interactive dashboard and a page where you can customize your own reports. There’s truly something for everyone in it.

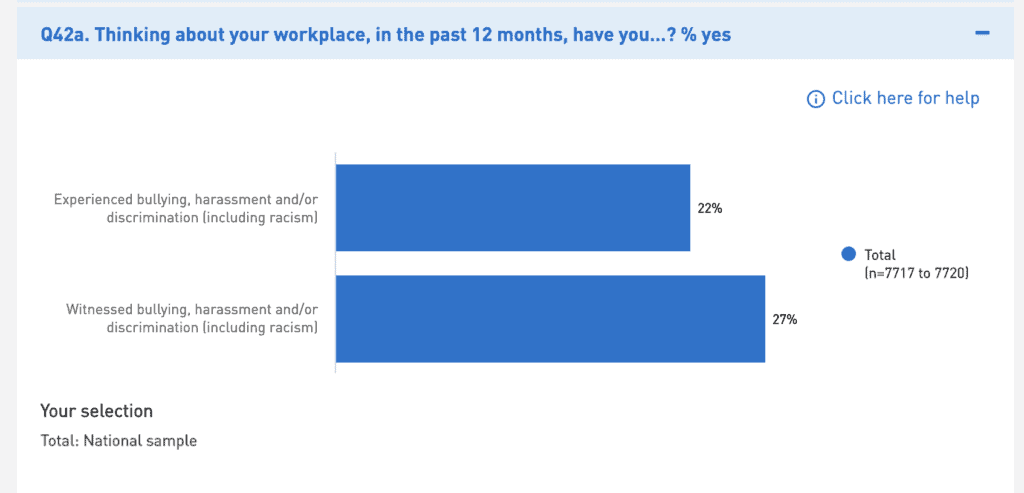

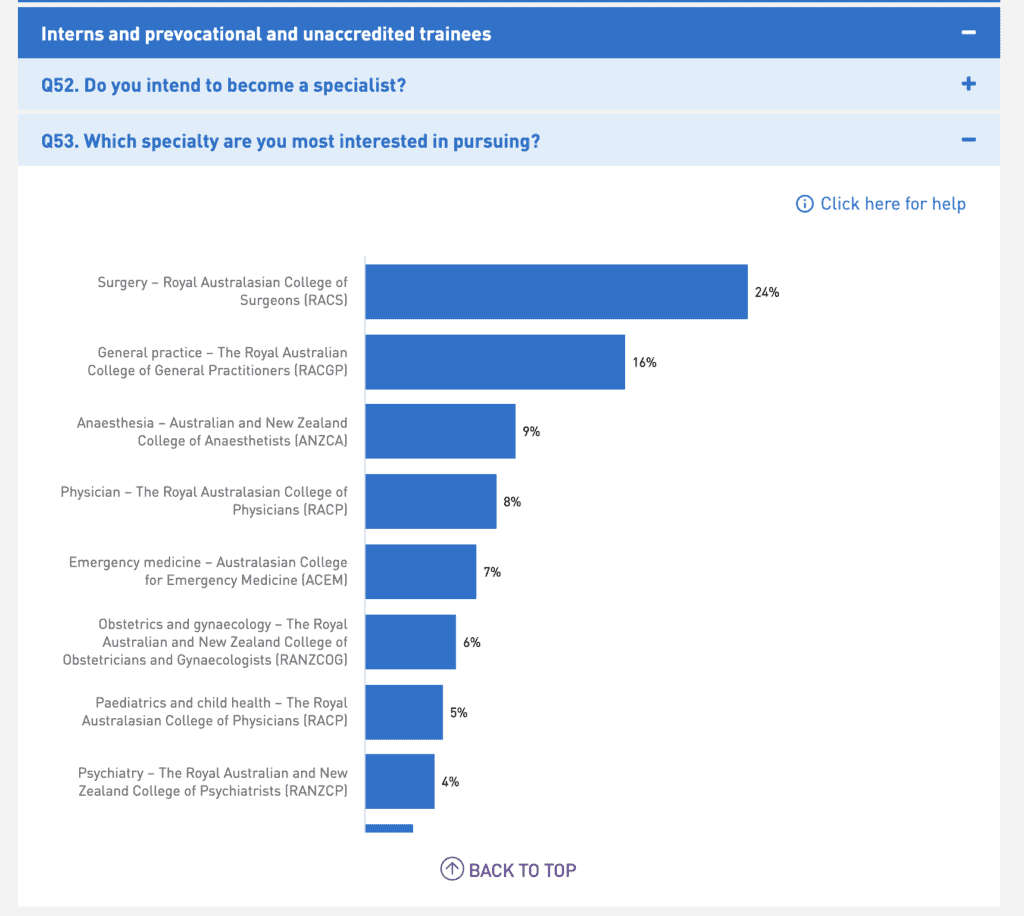

So, what are some of the key findings from this report? Key points from this survey are that greater than 75% of doctors in training are happy with their training and workplace, however, 22% had experienced some form of bullying, harassment or discrimination. Most doctors in training are working safe hours but a concerning amount are still working in excess of 60 hours and even 90 hours per week, with surgery being one particularly bad specialty for this. Contrastingly far too many doctors in training aspire to enter a specialty like surgery than there is the actual capacity or need for. The survey shows that individual doctor career plans are out of alignment with medical workforce planning. Finally, even though we do have information about how medical schools are now performing as part of the medical training pipeline this information is surprisingly absent from the survey.

Let’s drill a bit further into some of the key initial findings from the survey.

- Overall Impressions Of the Medical Training Survey.

- Overall Most Trainee Doctors Are Happy.

- Doctors In Training Are Still Working Too Much.

- There Are Still Too Many Doctors In Training Being Exposed to Bad Behaviour.

- Career Aspirations Greatly MisMatch the Reality.

- We Are Not Connecting the Dots (Yet) Between Medical School and Doctors In Training.

- Related Questions About the Medical Training Survey.

Overall Impressions Of the Medical Training Survey.

The Medical Training Survey will be run each year to get feedback from doctors in training in Australia (and in time their supervisors) to (according to the Medical Board of Australia):

- better understand the quality of medical training in Australia

- identify how best to improve medical training in Australia, and

- recognize and deal with potential issues in medical training that could impact on patient safety, including environment and culture, unacceptable behaviours and poor supervision.

It will take a while to assess the impact of this report. What we will need to see over time is the collection of data and the monitoring of trends to see whether the presence of the survey itself can spur on positive change.

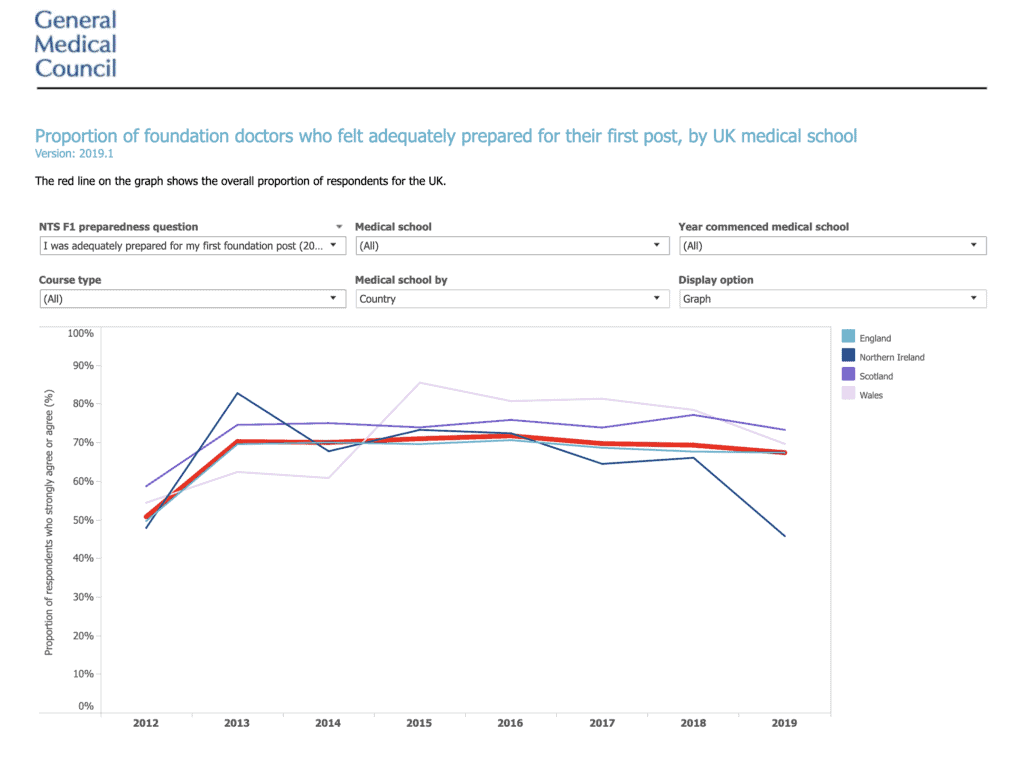

There is some hope that it might do that. As similar surveys which have been running in the United Kingdom for some time now have shown improvements on parameters such as the extent to which Foundation doctors felt adequately prepared for their posts by their medical school has improved over time.

Image from the UK medical training survey depicting a sharp rise in “preparedness” from 2012 to 2013 (previous surveys would show this trend as going upwards from a lower level, but the 70% appears to be a natural barrier to further improvement). Source gmc-uk.org

Overall Most Trainee Doctors Are Happy.

With all the negative stories associated with the lot of trainee doctors in Australia over the past few years. It may be tempting to conclude that trainee doctors in Australia are a deeply unhappy lot. However, that’s simply not the case.

And whilst, those stories should not be ignored and whilst there is empirical evidence of trainee doctors in Australia being exposed to adverse experiences in the workplace at unacceptable rates. This experience is thankfully not the experience of the majority.

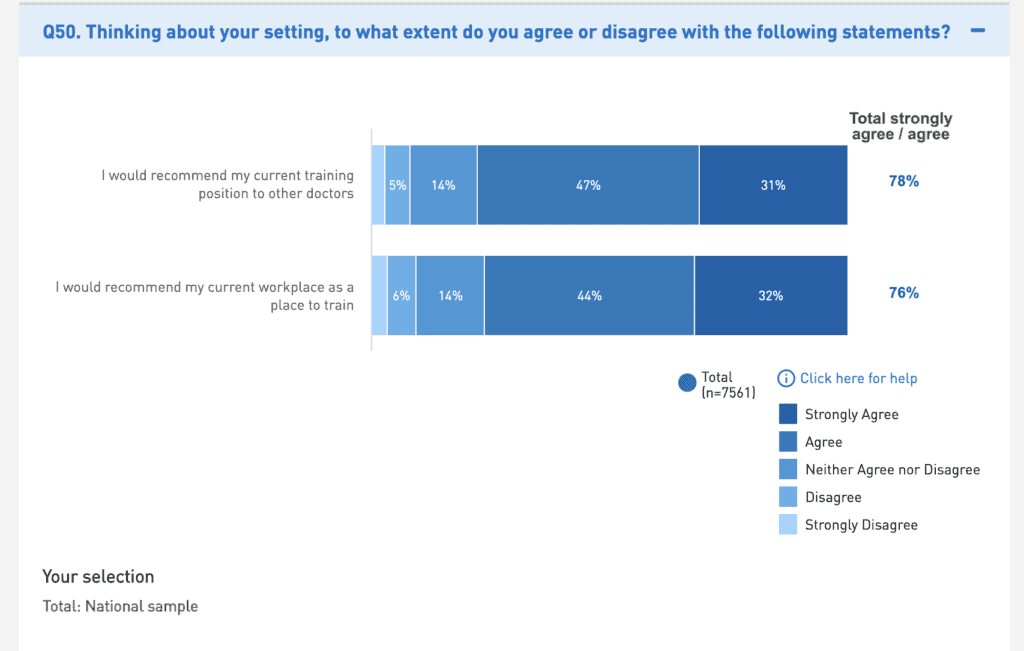

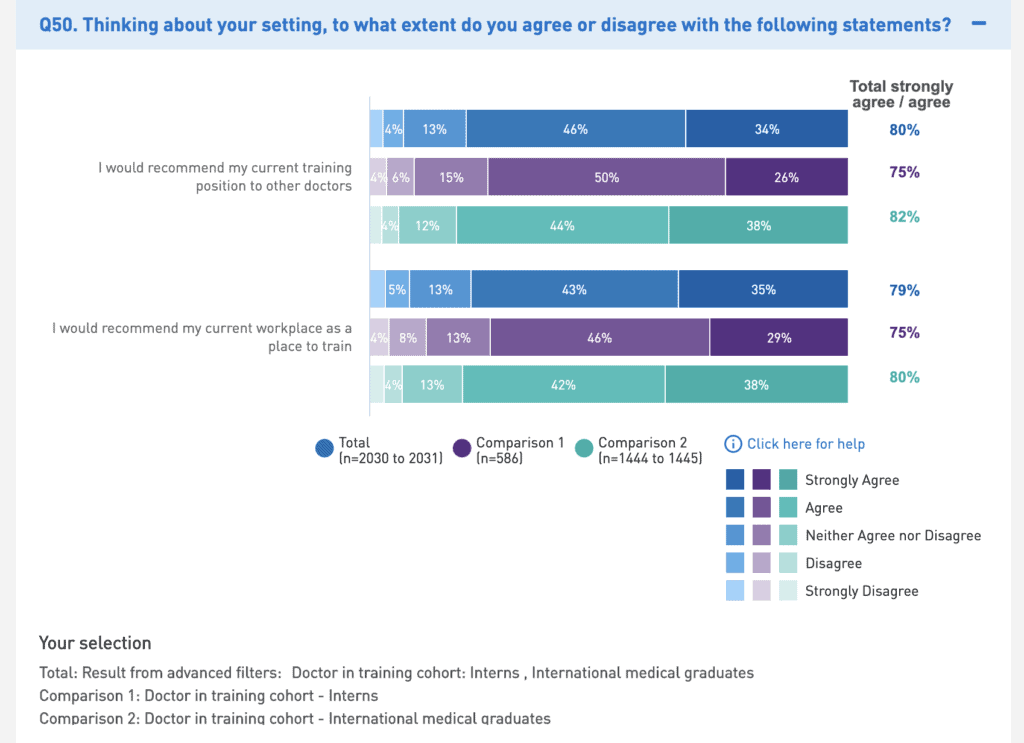

In fact, 78% of the survey respondents indicated that they would recommend their current training position to other doctors (agreed or strongly agreed), followed closely by 76% of respondents being comfortable recommending their workplace as a place to train (again agreed or strongly agreed).

International Doctors Are Even Happier According to the Medical Training Survey.

I get asked a lot by international doctors if hospitals in Australia are good environments for IMGs.

Here’s a table that shows you that overall IMGs are actually even happier than interns about their training post and workplace.

82% IMGs would recommend their training post to another doctor, compared to 75% of interns. And 80% of IMGs would recommend their workplace to another doctor, compared to 75% of interns.

Doctors In Training Are Still Working Too Much.

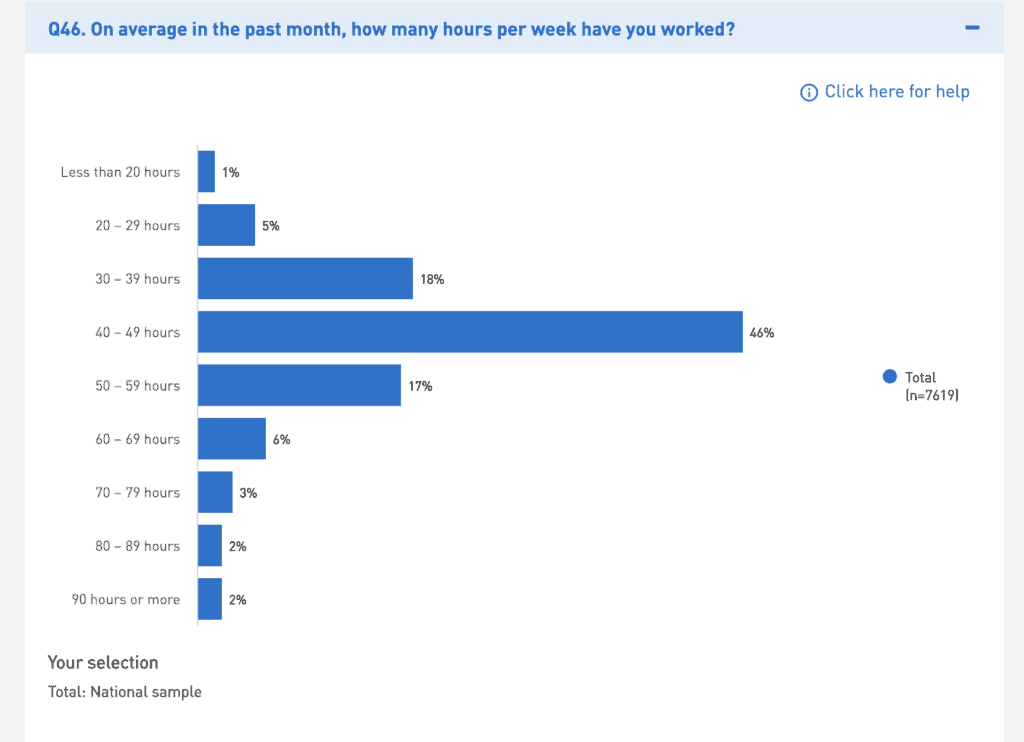

The survey shows that the majority of doctors in training are now working under 49 hours per week. However, 17% are in a risky area of working up to 59 hours a week and there are concerning outliers with 13% reporting working greater than 60 hours per week, including up to 90 hours or beyond.

What is also interesting is that whilst one might expect that excessive work hours are more of a problem for specialty trainees when one compares the figures between, say interns and specialty trainees the difference is the other way with 16% of interns working over 60 hours a week and only 12% of specialty trainees working over 60 hours per week.

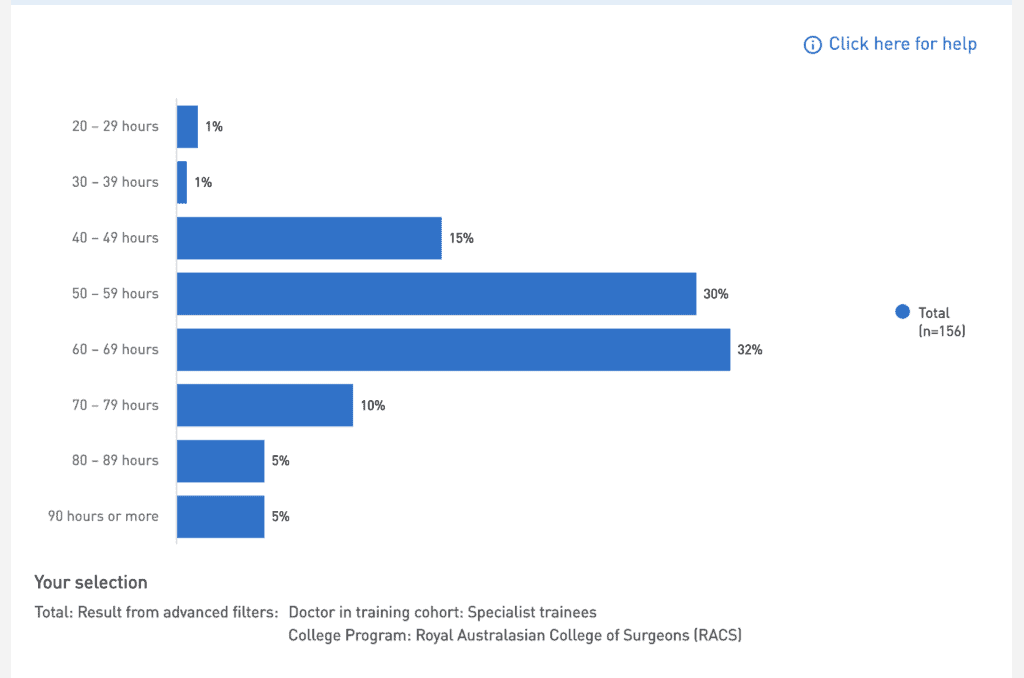

But if we go a bit more granular and check out a specialty like surgery, we see more of what we expect to see.

52% of RACS trainees report working greater than 60 hours a week. If you spot a worse group than this on the survey, I’d love to know about it.

Where Did That Unrostered Overtime Go?

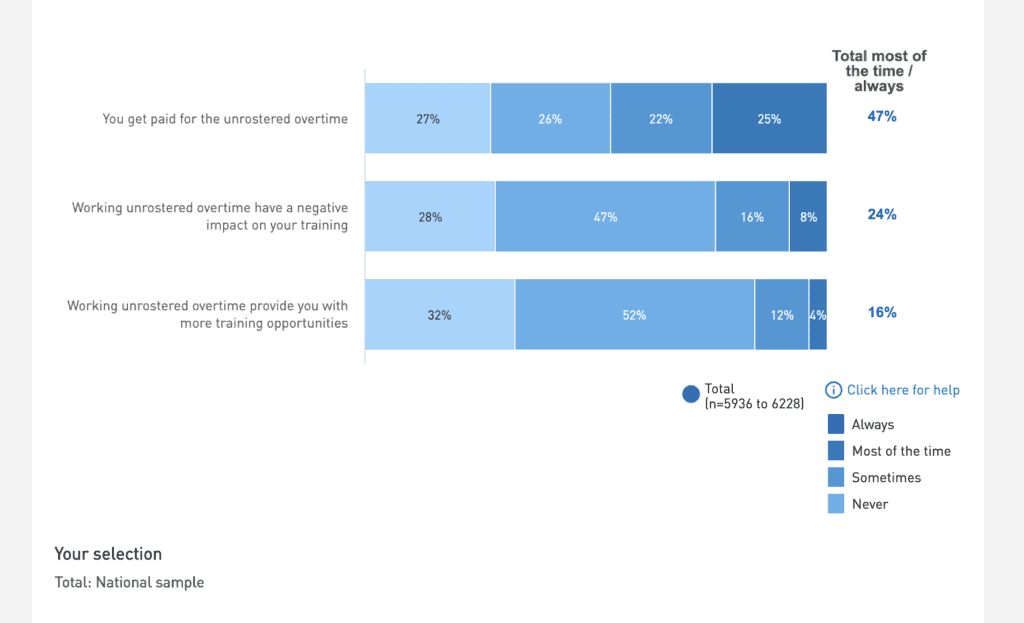

Also, only 47% of doctors in training report being paid for unrostered over time, which is a deep concern.

There Are Still Too Many Doctors In Training Being Exposed to Bad Behaviour.

22% of doctors in training report personal experience of bullying, harassment or discrimination and 27% report witnessing this. This is on part with other reports conducted around this issue, including one I helped write a few years back.

Similar to our report findings only 35% of the recipients and 29% of the witnesses reported reporting this behaviour. Which again is consistent with other studies. What is most worrying is the level of non-witness report as this is probably the key statistic to be focussing in on here.

If there is a silver lining to all of this it is that 52% of recipients who reported bullying, harassment or discrimination received a follow up to their report. Now 52% may not seem all that great. But this is actually a pretty good baseline result given what we know so far about the skills and capabilities of senior colleagues in handling the difficult issue of bullying, harassment and discrimination.

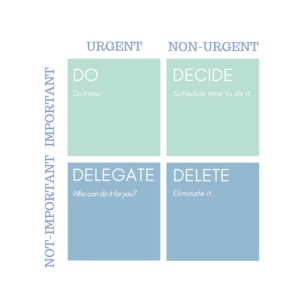

Career Aspirations Greatly MisMatch the Reality.

The MTS also included questions about career planning and intentions. Apparently 16% of Interns were unsure whether they did or did not have a training plan. In my book that means you don’t have a plan.

But check out the next table for an example of poor expectations management!

According to another medical workforce data set, the Health Workforce Australia, Medical Education and Training Dataset there were 1051 accredited surgical training positions in Australia. Now bear in mind that these 1051 positions aren’t just occupied by an individual doctor for one year but several years in order to complete a training program.

Contrast this with the fact that 26% of the interns, resident medical officers, senior residents and unaccredited trainees indicated they were most interested in pursuing surgery as a career. That’s a raw number of 351 of survey respondents alone. If we scaled it up to include those in these cohorts who did not complete the survey then we are probably talking 1500 to 2000, when the true capacity is around 200 to 300 per annum.

If we look at the other end of the spectrum we then see a specialty such as psychiatry which traditionally struggles to attract trainee doctors sitting at only 4% when in fact it has capacity for and needs more trainees than surgery. By the way, psychiatry also ranks in the top 5 professions for salary in Australia, along with Surgery. Just saying.

I was disappointed to see that this particular question was not asked of international medical graduates. This would be important information to have.

We Are Not Connecting the Dots (Yet) Between Medical School and Doctors In Training.

So the last key finding is really a non-finding. I was surprised to see with all the effort that went into making this survey right a failure to ask a really obvious question about the transition from medical school to being a doctor-in-training.

As we have alluded to in the United Kingdom survey this has been a key and consistent question in their national report. And it is an important one as we need to ensure that various parts of the medical training continuum are connecting with each other.

What is even more surprising is that this question does get asked in Australia. It is asked as part of a survey led by the Australian Medical Council but with the participation of the Medical Board of Australia in a separate survey called the Preparedness for Internship Survey. This survey showed that 74% of respondents (interns) felt their medical school training had been sufficient.

I believe it’s a mistake not to include this question in the national training survey as it helps us to connect some important dots with other questions. Hopefully, over time, the Medical Board will find a way of combining the results of both surveys.

I would encourage you to go and have a look at the survey yourself. Play around with it and see what you find.

In this post, I haven’t even touched on things like the differences between various States and Territories or touched on very much issues around specialty training or other specific groups.

I would love to get your feedback on the type of follow up post you would like to see to this one.

Related Questions About the Medical Training Survey.

Question. What is the Medical Training Survey (MTS)?

Answer. The Medical Training Survey is a national, profession-wide survey of all doctors in training in Australia. It is conducted in a confidential way to get national, comparative, profession-wide data. With the aim of strengthening medical training in Australia.

The survey is designed to be quick to complete and done on all manner of online devices and has the support of key stakeholders, such as doctors in training groups, employers, educators, the AMA and regulatory bodies.

Question. How does The Medical Training Survey happen?

Answer. The Medical Training Survey is open during August and September of each year, which coincides with the medical registration renewal period for most doctors in Australia.

The survey is run independently by research agency EY Sweeney. The survey is confidential, and data is gathered from online entry. Only aggregated data is ever reported, with the minimum threshold being ten (10) data points on any item and group to report back.

Question. Who can do the survey?

Answer. All doctors in training in Australia can do the survey. This includes interns, hospital medical officers, resident medical officers, non-accredited trainees, postgraduate trainees, principal house officers, registrars, specialist trainees and international medical graduates. Career medical officers who intend to undertake further postgraduate training in medicine can also participate.