For psychiatrists, Australia presents excellent job prospects. And it really has been this way for a long, long time. As a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) you can literally work anywhere in Australia and pretty much in any particular field, whether that be general psychiatry or something specific like a child and adolescent psychiatry or working in public or private or even both. Having spent a fair amount of my career filling positions in psychiatry I wanted to share my experience and advice with you.

In answer to the key question. How does one become a psychiatrist in Australia? Well, to work as a psychiatrist in Australia, you must obtain a Fellowship of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (the RANZCP). For locally-trained doctors, this involves completing a medical degree, at least one year internship, and a minimum of 5 years of training with the RANZCP. For specialist international medical graduates (IMGs) you must apply to the RANZCP for specialist recognition of your overseas training and experience.

Let’s look at psychiatry careers now in a bit more depth.

There are lots of job vacancies for both local as well as overseas trained psychiatrists in Australia.

There are lots of job vacancies for Psychiatrists in Australia (as there is in most other parts of the world). Mental health is a growth area, although arguably it’s more accurate to say that we are just now realizing how important it is relative to somatic medicine.

This all makes the task of those recruiting to Psychiatry positions tricky. I have had personal experience with this in past roles and have been quite successful in managing to put together strategies to fill positions. In Australia, it is quite common for recruiters to have a strategy of filling positions from international medical graduates (IMGs).

If you are an IMG Psychiatrist or even an IMG trainee in some cases. Then you will find that there are plenty of opportunities available to you in Australia. In fact, psychiatry is possibly the most accessible medical specialty for IMGs to access in this country.

In this blog post, I wanted to share my experience with you and highlight some tips. Here’s a summary of what we will discuss about the prospects of IMG doctors working in psychiatry in Australia:

- There are a number of vacant psychiatry consultant positions as well as vacant psychiatry trainee posts all year round in Australia.

- Unlike the specialist pathway for most other specialties, if you are an IMG psychiatrist you must have a job offer first before the RANZCP will consider your application, this is a good thing.

- The majority of specialist psychiatrists from Competent Authority countries will likely be found to have substantial comparability and specialist psychiatrists from other countries are likely to be found partially comparability although substantially comparable is not out of the question.

- If you are a trainee psychiatrist from the United Kingdom, Rep Ireland, Canada or the United States you will easily find a spare training post to fill under the competent authority pathway process.

- Whilst the prospects are very good you do need to be sincere, prepared to do some work to make yourself an attractive candidate and be prepared to be a little bit flexible, particularly in where you might work for your first job.

If you are excited so far then you may wish to fill out the quick survey below where we can provide you with an immediate quick appraisal of your prospects, as well as review your career profile in more depth for you.

Take Our Survey and See If you Qualify for a Free Call

[fluentform id=”9″]With that synopsis out of the way let’s dive further into the detail.

What does a psychiatrist do in Australia?

According to the RANZCP a psychiatrist, you will be able to:

listen to and provide expert care for vulnerable people and their families and work to prevent, diagnose and treat mental health conditions, lead teams of other doctors and health professionals, research to lead breakthroughs in psychiatry and mental health, foster new generations of psychiatrists, provide expert opinion to the community, government and courts.

How do Australian doctors become psychiatrists?

For an Australian doctor to become a psychiatrist they need to:

- complete a medical degree

- do on-the-job training in a hospital for at least 12 months, i.e. complete an internship

- enrol and complete training in the medical specialty of psychiatry with RANZCP.

Specialty training is a minimum of 5 years and leads to the Fellowship of RANZCP, the FRANZCP. Whilst the RANZCP still views the FRANZCP as a generalist qualification there are a number of Advanced Training programs or certificates that you can undertake to extend your knowledge in certain aspects of psychiatry, including child and adolescent, consultation-liaison, psychotherapy, forensics, old age to name a few.

How do overseas training programs align with the RANZCP?

Because being a psychiatrist is still considered to be mainly a generalist role in Australia most overseas specialty programs will align well with the RANZCP because these are also fairly generalist in their approach in the main as well.

There are sometimes some exceptions. For example, in the United States, it is possible to train primarily as a child and adolescent psychiatrist with little or no adult experience.

And occasionally when IMG psychiatrists apply to the RANZCP they are found to be a bit lacking in certain experiences that are a requirement here in Australia. Again, the most notable is the requirement to do at least 6 months of child and adolescent psychiatry training. This is however rarely a deal-breaker and usually only results in an extra recommendation of some additional time in child and adolescent psychiatry as part of the supervised component of the specialist pathway.

What are the chances of getting a job as a Psychiatrist in Australia?

Again, according to the RANZCP:

The likelihood of finding a job as a psychiatrist is very high. There are not enough psychiatrists to meet demand, especially in rural areas.

ranzcp.org

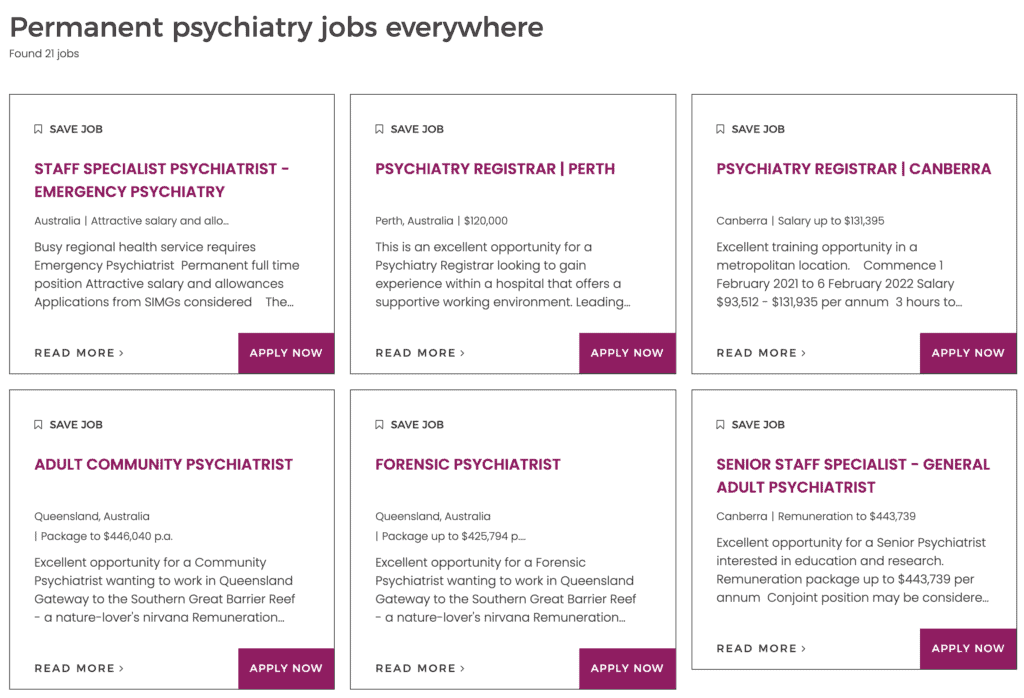

In fact you don’t really even need to look at rural areas of Australia. As you can see by this recent shot from one medical recruitment company website.

As you can see from above there are both consultant (Staff Specialist) roles available as well as trainee roles (Registrar) in major capital cities such as Perth and Canberra and regional coastal areas.

What can you earn working in Psychiatry in Australia?

The above image also gives you an indication of the salary packages, which for Consultant Psychiatrists range from $300K to the high $400K.

Sometimes specific additional incentives are applicable for psychiatrists and I was recently successful in obtaining a package of almost $500K for a particular psychiatrist. This is one of the reasons why being open to working in regional areas may make sense as your package may be better and generally your standard of living (particularly housing costs) will be much lower.

On top of the package for IMG Psychiatrists, employers are often also prepared to help with moving costs and may also pay for the cost of applying to the RANZCP from your professional development fund.

Whilst the pay packets for trainee psychiatry doctors are obviously not nearly as large as for consultants, you may still earn a bit more than the annual salary through performing overtime shifts (which are generally paid at 2x the hourly rate) and it is not unheard of employers also offering to cover some moving costs for trainee doctors as well.

What qualifications do you need to work in a Psychiatry job in Australia?

Your qualifications will be assessed by the RANZCP. In general, you will need some form of postgraduate qualification that is preferably at least 4 years duration.

For the UK/Ireland – MRCPsych combined with the CCT in the UK or CSCST for Ireland.

For Canada, you will require a Certificate in Psychiatry from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

For the USA, you will require a Certificate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.

For India, you will need a minimum of an MD or equivalent in Psychiatry, preferably you will do more than 3 years training. The addition of the Diplomate of the National Board is generally seen as a good addition.

For Sri Lanka, you will need a minimum of MD in Psychiatry recognised through the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine and be board certified as a psychiatrist via the Sri Lankan Medical Council.

What is the process for obtaining specialist recognition as a Psychiatrist in Australia?

The process is the same as for other specialist IMGs. Your educational qualifications and training as well as your specialist practice will be assessed by the RANZCP for comparability.

If you are deemed to be within 12 months of becoming a psychiatrist, you will be offered substantial comparability, which is the best outcome as this generally requires you to work as a specialist under peer review by current Fellows of the RANZCP for 12 months.

If you are deemed to be within 24 months of becoming a psychiatrist, you will be offered partial comparability. This is the next best outcome and generally requires you to work in an appropriate Advanced Trainee position, as well as under peer review by current RANZCP Fellows. It will also require you to undertake a range of assessments and activities as well as sit for written and clinical examinations.

If you are not deemed to be able to become a psychiatrist within 24 months you will be found not comparable. This means that you need to consider alternative pathways for registration and working in Australia.

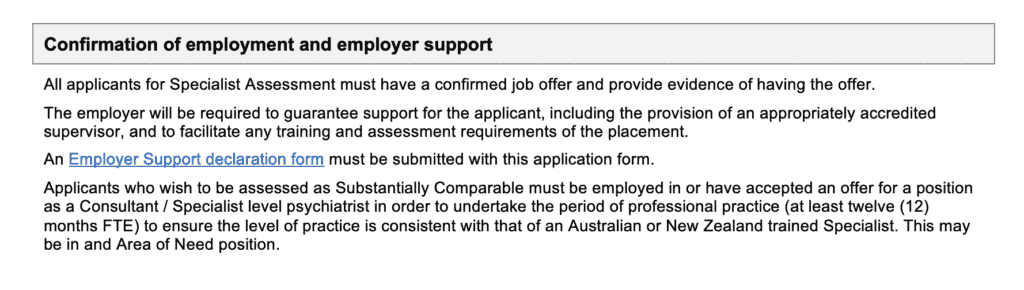

One key difference from the process of specialist assessment for other colleges is that the RANZCP requires you to have an offer of an appropriate position first before considering your specialist pathway application.

Whilst this may seem initially restrictive it is probably better. Because it reduces the number of specialist IMGs who are deemed comparable but are unable to gain an appropriate job offer. It also means that you are more likely to be supported by your employer to go through the RANZCP assessment process.

Whilst it is not absolutely guaranteed. Being interviewed successfully for a position as a psychiatrist in Australia will generally mean that the RANZCP will also find you comparable.

What types of comparability outcomes are likely for international psychiatrists in Australia?

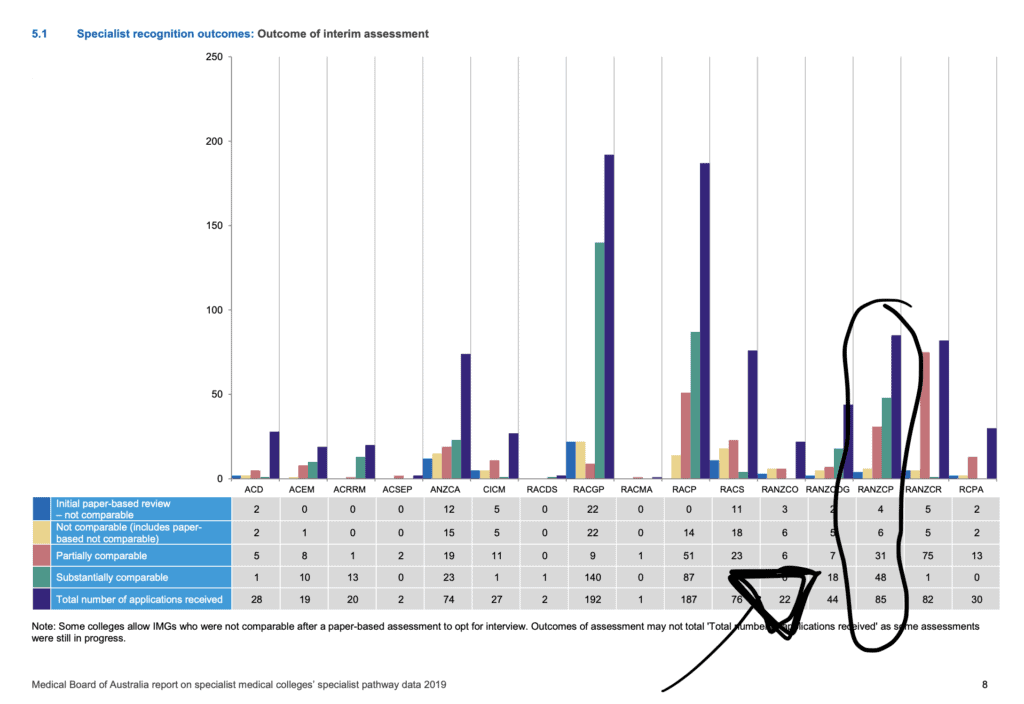

As can be seen in the images below taken from the most recent Medical Board of Australia report the majority of specialist IMG applications to the RANZCP are deemed substantially comparable with a significant number deemed partially comparable and only a small number seen as not comparable.

Does your country of training have any impact on your prospects for psychiatry jobs in Australia?

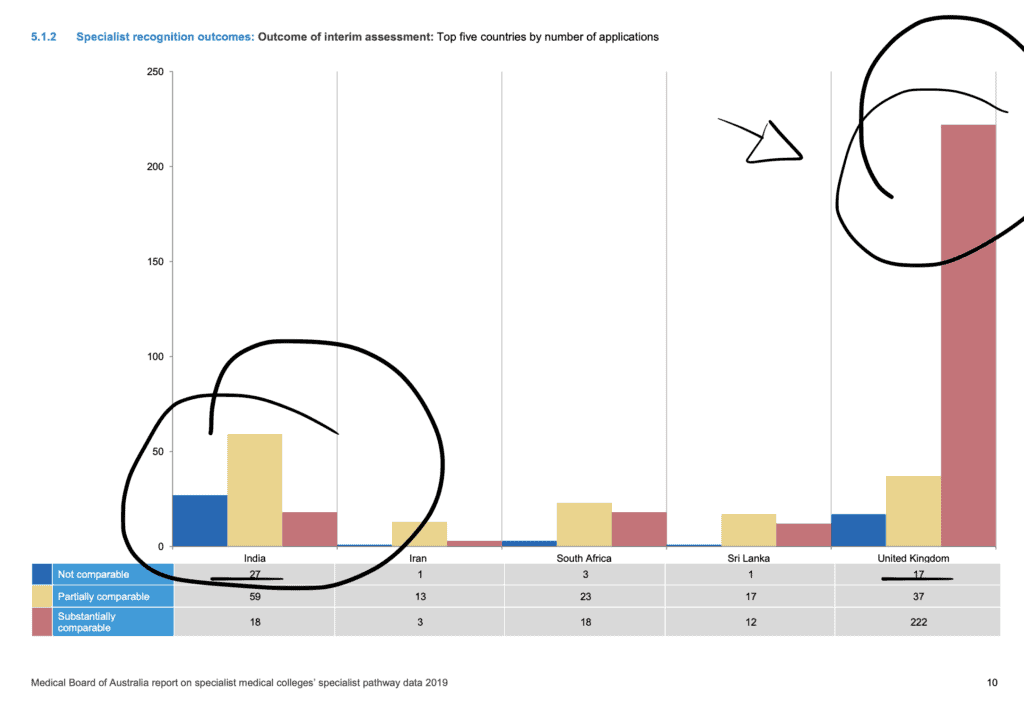

Whilst we don’t have figures by country of IMG versus the RANZCP assessment process it’s my experience that specialist psychiatrists from the competent authority countries are generally found to be substantially comparable. Specialist psychiatrists from other countries are more likely to be found substantially comparable, however, it depends on your individual circumstances and it is not uncommon for specialist psychiatrists from India, Sri Lanka, and South Africa to be found substantially comparable at times.

Empirical evidence for this exists when you look at the overall comparison between specialists from India and the UK in the same report.

What do you need to demonstrate if you want to work as a Psychiatry Trainee in Australia?

In order to convince an employer that you are suitable to work in a trainee psychiatry role you generally need some prior psychiatry trainee experience in your own country.

Because the process of becoming registered under the competent authority pathway is more streamlined and because the training programs in the competent authority countries are similar to that in Australia, trainee doctors with psychiatry experience in the UK, Ireland, Canada, or the US tend to be preferred by Australian employers when it comes to filling vacant trainee positions that have not been able to be filled by local graduates.

Whilst it is not impossible for trainee psychiatry doctors from other countries to also obtain posts it is more difficult as the process of gaining registration is more complex. If you have significant experience as a trainee psychiatrist, you may be able to obtain a position for a maximum of 2 years under the short-term specialist medical training pathway.

Is there recognition of prior learning for IMG trainees?

Colleges have become better at assessing trainee doctors from other countries for recognition of prior learning (RPL). In fact, I recently assisted a trainee doctor from the UK to obtain 2 years and 7 months from their 5-year RANZCP psychiatry training program.

That being said RPL generally reduces the amount of experience you may have to undertake and doesn’t normally excuse you from the key RANZCP examinations. The end effect may be to compact the number of assessment requirements you need to complete in the remaining time.

Take Our Survey and See If you Qualify for a Free Call

[fluentform id=”9″]Some Tips For Securing A Psychiatry Post In Australia.

Thus far it probably sounds like being able to work as a psychiatrist in Australia is a bit of a laydown misere. And whilst it is true that psychiatry is one of the top medical specialties that employers are regularly trying to fill in Australia. It is not just a matter of sending off a quick email with a CV that hasn’t been updated in a few years. There is still a bit of work ahead of you.

Here are my recommendations for what you should do if you are keen on working in psychiatry in Australia.

- First off, ensure that you have an up to date and employer-friendly resume. This should be around 3 to 6 pages depending on your experience. And you should make sure wherever possible you tailor it to individual job openings. If you are needing tips on your resume (CV) we have several posts about this matter on the blog, as well as a service for helping you redo your resume if you would like some assistance with this key document.

- Second, if you are going to apply for a specialist role it’s worth reviewing the documentation on the RANZCP website to see if you will be eligible. And we also have a handy free short course on the specialist pathway that you can take as well.

- Third, whilst it is sometimes possible to score a post in a major Australian city like Sydney or Melbourne. If you are too prescriptive about where you want to work you are very likely to severely limit your chances and miss out. Bear in mind that once you complete your first year or two under supervision you will normally then be eligible for either specialist registration or general registration. At this point, you can often move jobs and locations more easily. So the key message here is to be open to all possibilities for your first position. You may even like working in regional Western Australia or the North West Coast of Tasmania!

- Fourthly. And following on from the above point. Whilst it is possible to directly approach employers for posts in psychiatry. This is only really about 50% of the job market. It is often unclear which publicly advertised positions are open to IMG doctors and employers are also often directly working with medical recruitment companies to fill vacant spots. For this reason, I generally recommend that you do contact a medical recruitment company if you believe you are eligible for a specialist position as an IMG or a trainee psychiatry doctor from one of the competent authority countries. If you fill in the survey below we can put you in contact with our recommended medical recruitment company.

- Fifth and finally. If an employer is interested in you they will invite you for an interview. This may be the first time you have sat a job interview in sometime and will almost certainly be the first job interview you have sat in Australia. You may be a little nervous and it will be important to give an impression. You may therefore want to consider getting some assistance by way of some interview coaching beforehand.

Related Questions

Can overseas doctors work as a psychiatrist in Australia?

Do psychiatrists make good money?

What qualifications do you need to become a psychiatrist in Australia?

1. complete a medical degree.

2. do on-the-job training in a hospital for at least 12 months (internship).

3.enrol and complete training in the medical specialty of psychiatry with RANZCP.

Qualified psychiatrists from other countries apply to the RANZCP for assessment of their specialist recognition under the specialist pathway for medical registration.

How much does a consultant psychiatrist earn in Australia?

Psychiatrists also do relatively well in the private sector and you can potentially earn far more than in the public sector and up to $800,000AUD. As we have highlighted in this related blog post, psychiatrists are 5th on the list of top ten professions by earnings according to the Australian Tax Office.

How long does it take to become a psychiatrist in Australia?

What field of psychiatry makes the most money?

It’s hard to say which actual field of psychiatry makes the most money. There are certain subspecialties in psychiatry that are more limited to working in public hospital settings, for e.g. consultation-liaison psychiatry, so these consultants will earn a bit less than someone working in the private sector. Subspecialties that lend themselves best to private sector work, and which will therefore, have higher earning potentials, including forensic psychiatry and adult psychiatry.